Decoding Chinese Tones: Your Essential Guide to Understanding and Mastering Mandarin Pronunciation

Learning Mandarin Chinese opens doors to one of the world's richest cultures and most dynamic economies. However, many learners quickly discover that the tonal nature of Chinese presents a unique challenge. Unlike English, where pitch typically indicates emotion or question formation, in Mandarin Chinese, Chinese tones fundamentally change word meanings. This comprehensive guide will walk you through what Chinese tones are, why they matter so much, and how to master them effectively. Whether you're just starting your Mandarin journey or looking to refine your pronunciation, understanding Chinese tones is essential for being understood and understanding others.

- I. Why Tones Matter: The Heartbeat of Spoken Mandarin

- II. Meet the Mandarin Tones: A Detailed Breakdown (4+1)

- III. Tones in Conversation: How They Change with Tone Sandhi

- IV. Starting Your Tone Journey: Foundational Learning Steps

- V. Common Pitfalls for Learners (and How to Avoid Them)

- VI. Expanding Your Understanding: FAQs and Broader Context

- 1. Definitional Q: What truly distinguishes the 'neutral tone' from the four main Mandarin tones?

- 2. Grouping Q: Beyond Mandarin, what other major Chinese varieties rely heavily on tones?

- 3. Comparative Q: How does the challenge of learning Mandarin tones compare to learning grammatical gender in languages like French or German?

- 4. Boolean Q: Is it possible to communicate basic ideas in Mandarin without perfect tones?

- VII. Integrating Tones Seamlessly: The Path Towards Natural Mandarin Speech

I. Why Tones Matter: The Heartbeat of Spoken Mandarin

The tonal system is not merely an aesthetic feature of Mandarin—it's the very foundation of intelligible speech. Mastering Chinese tones is non-negotiable for anyone serious about communicating effectively.

1. What Are Tones, Exactly? Pitch That Defines Meaning

In Mandarin Chinese, Chinese tones are lexical pitch contours that distinguish one word from another. Think of them as melodic patterns attached to syllables that determine their meaning. While English speakers use pitch variation to express emotion or indicate questions versus statements, Mandarin uses pitch to distinguish between entirely different words. This fundamental difference makes Chinese tones essential rather than optional in Chinese. Without the correct tone, you might be saying an entirely different word than you intend.

Each syllable in Mandarin carries its own tone, and these tones are represented in the Pinyin romanization system with specific Chinese tone marks above vowels. This system helps learners visualize the pitch changes needed for correct pronunciation.

2. The Proof: How One Syllable ("Ma") Tells Five Different Stories

The classic example that demonstrates the critical importance of Chinese tones is the syllable "ma," which can represent five completely different meanings depending solely on its tone:

-

mā (妈): First tone (high and level) means "mother"

-

má (麻): 2nd tone (rising) means "hemp" or "numb"

-

mǎ (马): 3rd tone (falling then rising) means "horse"

-

mà (骂): Fourth tone (falling sharply) means "to scold"

-

ma (吗): Neutral tone (unstressed and light) is a question particle

This single example powerfully illustrates why Chinese tones cannot be ignored. Saying "I want to ride a horse" with incorrect tones might accidentally become "I want to ride my mother"—a mistake no learner wants to make! Correct Chinese tones are essential for basic comprehension.

3. Tones in Writing: Understanding Pinyin Tone Marks

Hanyu Pinyin, the standard romanization system for Mandarin Chinese, uses diacritical marks placed above vowels to indicate tones. These visual cues help learners remember and practice the correct pronunciation of pinyin tones:

-

Tone 1: Macron (ˉ) as in ā

-

2nd tone: Acute accent (´) as in á

-

3rd tone: Caron/háček (ˇ) as in ǎ

-

Tone 4: Grave accent (`) as in à

-

Neutral tone: No mark (a)

When learning new vocabulary, these Chinese tone marks are crucial visual reminders of how each syllable should be pronounced.

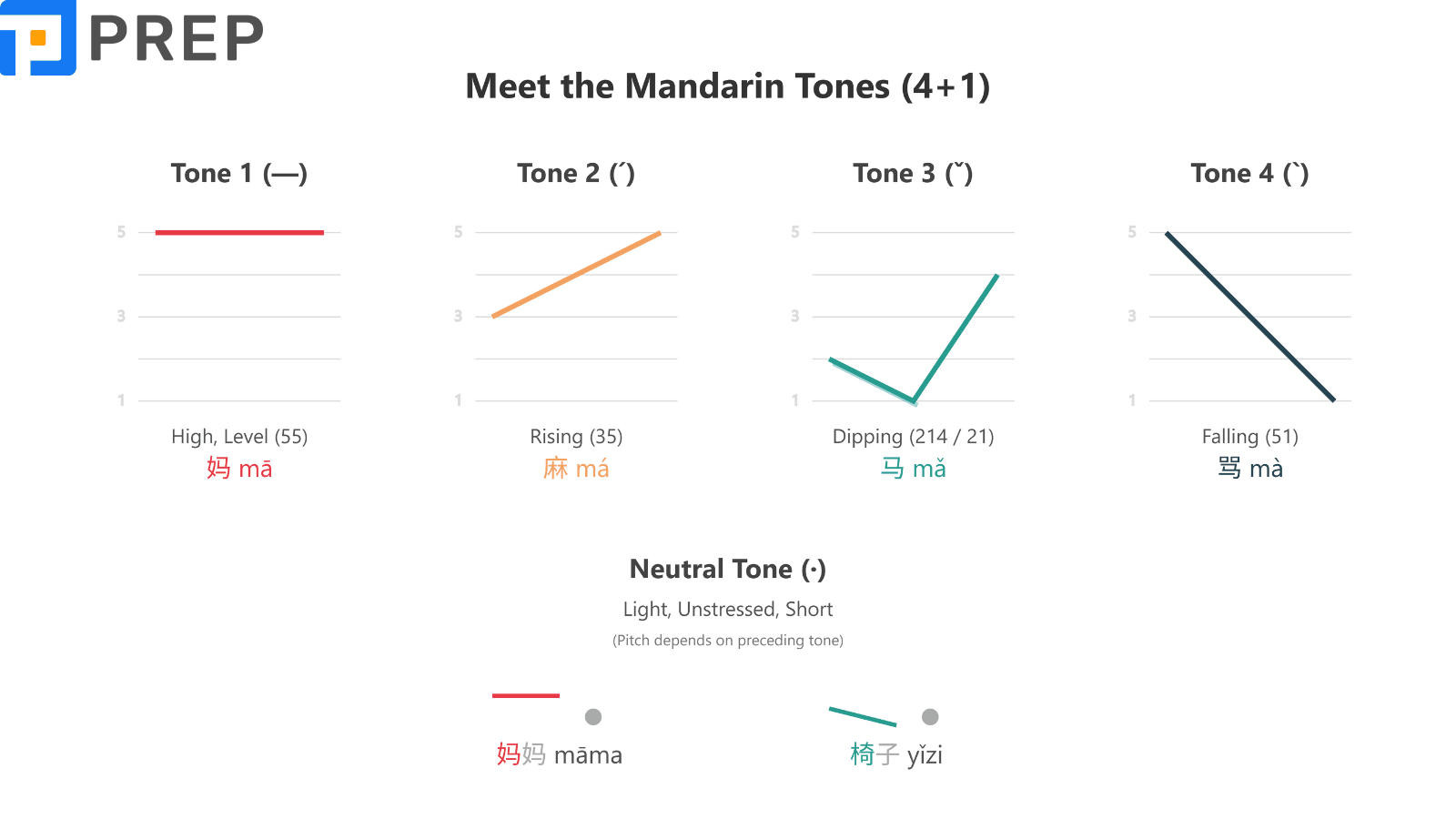

II. Meet the Mandarin Tones: A Detailed Breakdown (4+1)

Now that we understand why Chinese tones matter, let's explore each one in detail. How many tones in Mandarin? There are four main tones plus a neutral tone, each with distinctive characteristics that we'll break down individually.

1. Tone 1 (—): The High, Level Flight (Pitch 55)

The first tone in Chinese four tones is high, level, and sustained. Imagine holding a single musical note at a consistently high pitch without wavering. When producing the first tone, keep your voice elevated and steady from beginning to end, with no rise or fall in pitch.

Think of it as similar to the monotone sound of a flat line on a heart monitor or the steady drone of an airplane in level flight. Your voice should maintain the same high pitch throughout the syllable without dipping or rising at all.

Some common examples of first tone words include:

-

妈 (mā) - mother

-

一 (yī) - one

-

高 (gāo) - high/tall

-

吃 (chī) - to eat

To practice this tone effectively, try elongating the sound while maintaining the steady high pitch. Don't let your voice trail off or dip at the end.

2. Tone 2 (´): The Questioning Rise (Pitch 35)

The 2nd tone in Chinese four tones starts at a medium pitch and rises decidedly upward, similar to how English speakers raise their voice when asking a question like "What?" or expressing surprise. This tone begins at a mid-range pitch and moves upward in a clear, rising motion.

When pronouncing the 2nd tone, start comfortably in your mid-pitch range and rise decisively to a higher point. The movement should feel like an upward inflection or the sound of asking a yes/no question in English.

Common examples of 2nd tone words include:

-

麻 (má) - hemp/numb

-

来 (lái) - to come

-

忙 (máng) - busy

-

学习 (xuéxí) - to study

For effective practice, compare the difference between saying "what" as a statement versus "what?" as a question. The rising intonation in the question form closely resembles Mandarin's 2nd tone.

3. Tone 3 (ˇ): The Dipping Valley (Pitch 214) & The "Half-Third"

The 3rd tone is often considered the most challenging of the Chinese tones for beginners. In its full form, it has a complex contour: starting at mid-low, dipping to the lowest point, then rising again (though not as high as the second tone). This creates a distinctive "dipping" or "scooping" sound that resembles a shallow valley.

Crucially, this full dipping pattern (214) is relatively rare in natural speech. In most contexts—specifically before any other tone (first, 2nd tone, fourth, or neutral tone)—the 3rd tone is pronounced as what's called a "half-third," where only the initial low dip (21) is articulated without the rising portion. This shortened version is actually much more common in everyday conversation and sounds more natural to native speakers.

When pronouncing the 3rd tone, focus on hitting that low point. The key characteristic is the low dip, not the optional rise that follows.

Common examples of 3rd tone words include:

-

马 (mǎ) - horse

-

好 (hǎo) - good

-

我 (wǒ) - I/me

-

水 (shuǐ) - water

Practice this tone by exaggerating the dipping motion initially, then work on recognizing when to use the full dip-rise versus the more common half-third.

4. Tone 4 (`): The Sharp Command (Pitch 51)

The fourth tone in Chinese four tones starts high and drops sharply and quickly. It has a decisive, forceful quality, similar to giving a firm command like "Stop!" or making a definitive statement. This tone begins at the top of your pitch range and falls rapidly to the bottom.

When pronouncing the fourth tone, start high and drop your pitch firmly and quickly. The motion should be energetic and assertive, like chopping downward with your hand. Make sure to start from a high point to give yourself enough range for the dramatic fall.

Common examples of fourth tone words include:

-

骂 (mà) - to scold

-

去 (qù) - to go

-

大 (dà) - big

-

看 (kàn) - to look/see

To practice effectively, try comparing the fourth tone to an emphatic "No!" in English, where your voice falls sharply from high to low.

5. The Neutral Tone (No Mark): The Quick, Unstressed Syllable

The neutral tone in Chinese tones is sometimes called the "fifth tone," though it's not a distinct pitch contour like the others. Rather, it's characterized by its brevity, lack of stress, and relatively weak articulation. The actual pitch of a neutral tone syllable depends largely on the tone of the preceding syllable.

Neutral tones commonly appear in:

-

Grammatical particles like 的 (de), 了 (le), and 吗 (ma)

-

The second syllable of many reduplicated words

-

Certain syllables in common words that have become unstressed through frequent usage

Examples of words with neutral tone syllables include:

-

妈妈 (māma) - mom

-

爸爸 (bàba) - dad

-

椅子 (yǐzi) - chair

-

明白 (míngbai) - to understand

The key to pronouncing neutral tones correctly is to make them quick, light, and unstressed while letting the preceding syllable determine their relative pitch.

III. Tones in Conversation: How They Change with Tone Sandhi

While understanding individual Chinese tones is essential, equally important is understanding how these tones change in connected speech. These predictable tone modifications, known as "tone sandhi," make Mandarin sound natural and flowing rather than robotic.

1. Understanding Tone Sandhi: Why Tones Adapt

Tone sandhi refers to the phonological changes that occur when certain Chinese tones appear next to each other in connected speech. These changes aren't random but follow specific patterns that make pronunciation more fluid and natural. Think of tone sandhi as the bridges between individual tones that allow for smoother transitions in speech.

2. The Golden Rule: Smoothing Out Double Third Tones (3+3 → 2+3)

The most important tone sandhi rule in Mandarin involves consecutive 3rd tone syllables. When two 3rd tone syllables occur back-to-back, the first one changes to a 2nd tone (rising) in pronunciation. This rule is applied automatically by native speakers and is essential for natural-sounding Mandarin.

For example:

-

你好 (nǐ hǎo) is pronounced as if it were "ní hǎo"

-

很好 (hěn hǎo) is pronounced as if it were "hén hǎo"

-

洗澡 (xǐzǎo) is pronounced as if it were "xízǎo"

Importantly, the written form in Chinese pinyin tones does not change—only the pronunciation does. This change makes speech flow more naturally by avoiding the awkward double-dipping that would occur with two consecutive 3rd tones.

3. Common Changes for "Yī" (一) and "Bù" (不)

Two extremely common words in Mandarin—一 (yī, "one") and 不 (bù, "not")—have special tone sandhi rules:

-

一 (yī) is first tone when used alone, at the end of a phrase, or when counting. It becomes 2nd tone (yí) before a fourth tone word (e.g., 一样 yíyàng). It becomes fourth tone (yì) before first, 2nd tone, or 3rd tone words (e.g., 一天 yìtiān).

-

不 (bù) is normally fourth tone but changes to 2nd tone (bú) when followed by another fourth tone word (e.g., 不是 búshì).

These changes occur naturally in native speech and greatly contribute to the rhythmic flow of Mandarin.

4. The "Half-Third" Tone Revisited: When to Use It

As mentioned earlier, the half-3rd tone (just the low dip without the rise) is extremely common in connected speech. Use this shortened version when a 3rd tone syllable appears before any other tone (first, 2nd tone, fourth, or neutral tone).

This adjustment makes your speech sound much more natural and fluid. Native speakers rarely use the full rising-falling-rising contour of the 3rd tone in everyday conversation except when emphasizing a word or speaking in isolation.

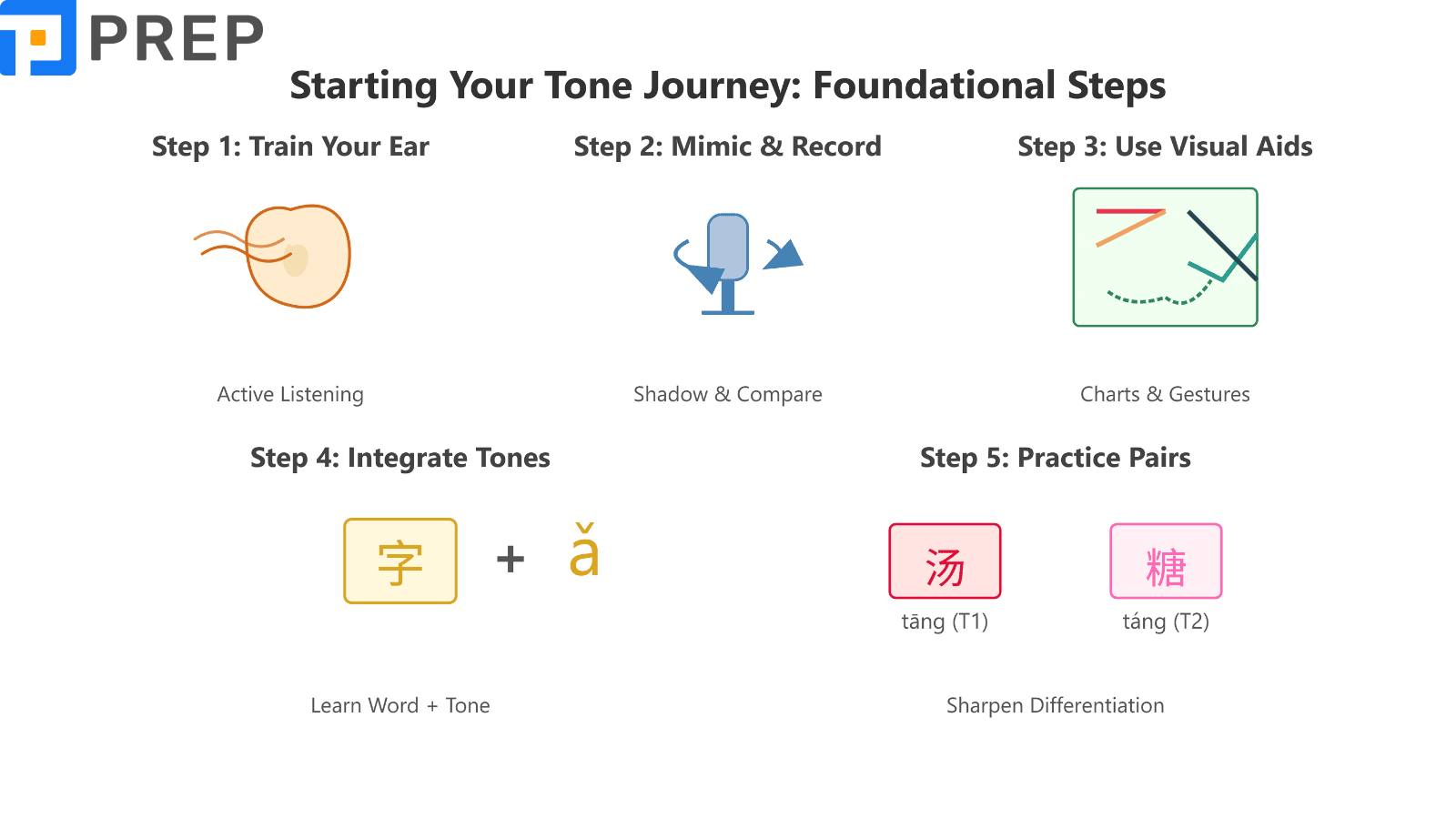

IV. Starting Your Tone Journey: Foundational Learning Steps

Now that we've explored the mechanics of Chinese tones and their interactions, let's focus on practical strategies to help you master them. The following steps provide a clear pathway for beginners to develop strong tonal awareness and accuracy.

1. Step 1: Train Your Ear - Active Listening is Non-Negotiable

Before you can produce Chinese tones accurately, you must be able to hear them clearly. Develop your ear through dedicated listening practice focusing specifically on tonal distinctions. Listen to native speakers in podcasts, videos, or language learning resources, paying particular attention to the pitch patterns. Try to identify which tone is being used by focusing on the melodic contour of each syllable, not just the consonants and vowels.

Active listening means consciously analyzing what you hear rather than passively absorbing it. Challenge yourself to identify tones in real-time as you listen to natural speech.

2. Step 2: Mimic and Record - Compare Your Sound

One of the most effective techniques for tone mastery is shadowing—immediately repeating what you hear from a native speaker, mimicking not just the sounds but the exact pitch contour. Record yourself doing this, then listen back and compare your pronunciation with the original.

This comparison allows you to objectively identify discrepancies between your pronunciation and native speech. Many learners are surprised to discover that what they think they're saying doesn't match what they're actually producing. Regular recording and comparison helps bridge this gap between perception and production.

3. Step 3: Use Visual Aids - Connect Sound to Shape

Visual representations can significantly enhance your understanding of Chinese tones. Utilize resources like a Mandarin tones chart showing the pitch patterns of each tone, Chinese pinyin tones with tone marks, or even physical hand gestures that trace the shape of each tone in the air.

A good tone chart creates a multi-sensory connection between what you hear, what you see, and eventually what you produce. Many learners find that tracing the physical movement of each tone with their hand while speaking helps internalize the correct pitch patterns.

4. Step 4: Integrate from Day One - Learn Vocabulary WITH Tones

Perhaps the most crucial habit for long-term tone mastery is learning every new word complete with its correct tone(s). Never separate a syllable from its tone—they are inseparable aspects of the same word. Learning vocabulary without tones is like learning only half the word.

When you encounter a new word, immediately note its Chinese tone marks and practice saying it with the correct pitch patterns from the very beginning. This approach prevents the formation of bad habits that become increasingly difficult to correct later.

5. Step 5: Practice Minimal Pairs - Sharpen Differentiation

Minimal pairs are words that differ only in tone but are otherwise identical. Practicing these pairs helps train your ear and voice to distinguish subtle tonal differences. For example:

-

tāng (汤, soup) vs. táng (糖, sugar)

-

mǎi (买, to buy) vs. mài (卖, to sell)

-

shì (是, to be) vs. shí (十, ten)

Regular practice with minimal pairs trains your brain to recognize and produce these critical distinctions automatically. Focus particularly on pairs involving tones you find most challenging to differentiate.

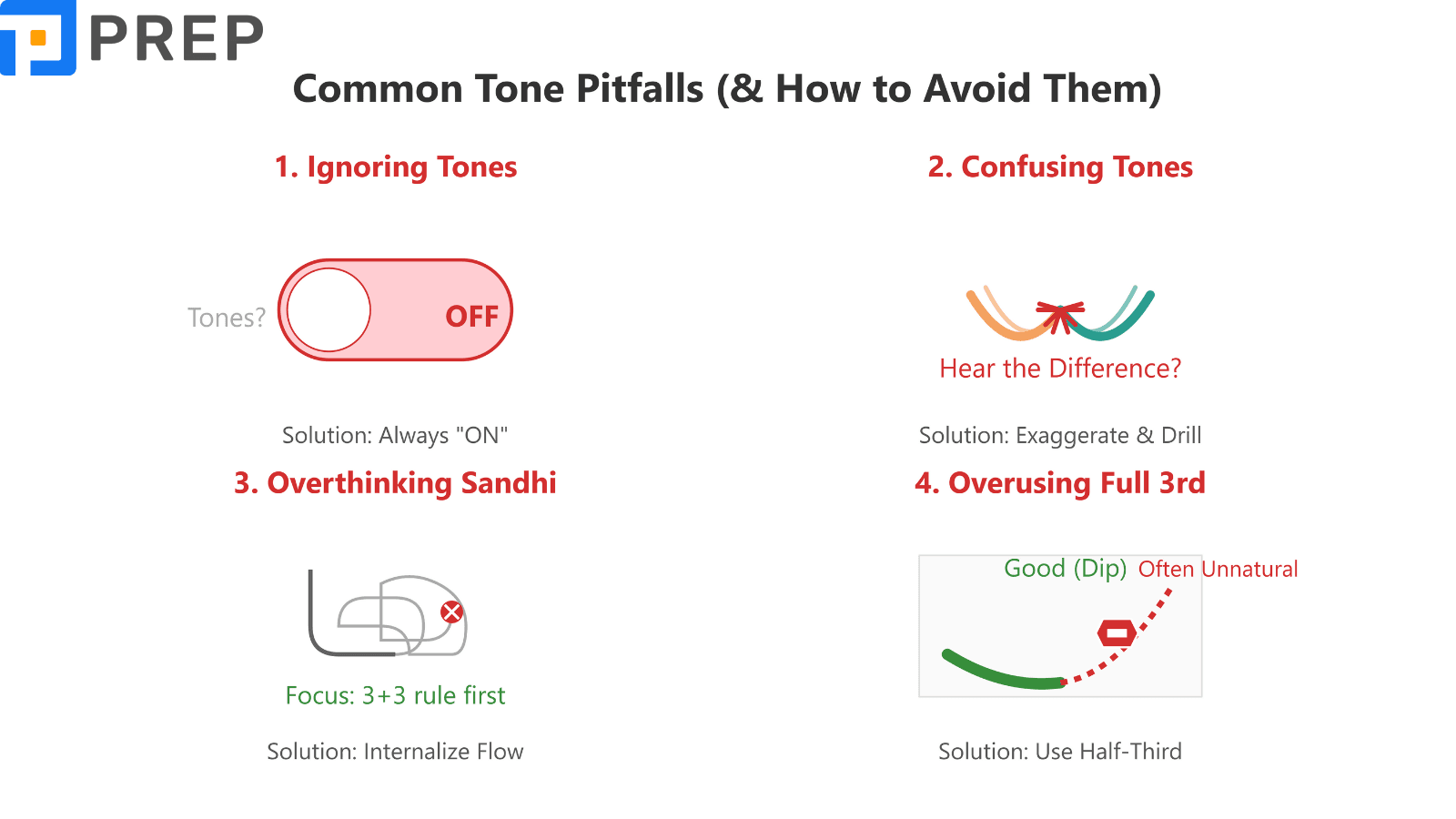

V. Common Pitfalls for Learners (and How to Avoid Them)

Learning Chinese tones presents specific challenges that many students encounter. Being aware of these common pitfalls can help you navigate around them more effectively.

1. Pitfall 1: Underestimating or Ignoring Tones

Many beginners make the mistake of treating Chinese tones as an optional feature rather than an integral part of each word. This approach inevitably leads to confusion, miscommunication, and frustration when native speakers struggle to understand even simple phrases.

The solution is straightforward: acknowledge from day one that tones are non-negotiable. Commit to learning and practicing tones with every new word, and never allow yourself to "just focus on the sounds first and add tones later." This disciplined approach pays enormous dividends in long-term comprehensibility.

2. Pitfall 2: Confusing Similar-Sounding Tones (esp. 2nd & 3rd)

Certain tone pairs present particular challenges for non-native speakers. Many learners struggle to differentiate between the 2nd tone (rising) and 3rd tone (dipping then rising), especially in rapid speech. Similarly, the distinction between first tone (high level) and fourth tone (falling) can be troublesome initially.

To overcome this challenge, practice exaggerating the tones when you're learning—make the 2nd tone rise dramatically and ensure the 3rd tone dips very low before any rise. Focus on minimal pairs that contrast these problematic tones, and dedicate extra listening practice to distinguishing between them.

3. Pitfall 3: Misapplying or Overthinking Tone Sandhi

Some learners, after learning about tone sandhi rules, attempt to consciously apply all these changes during speech. This typically results in hesitation, unnatural pausing, or incorrect application, disrupting the flow of conversation.

Instead of overthinking tone sandhi, focus first on mastering the most critical rule—the 3rd tone change (3+3 → 2+3). Allow the other patterns to develop more naturally through extensive listening and mimicry of native speech. Tone sandhi should eventually become automatic rather than requiring conscious calculation during speech.

4. Pitfall 4: Pronouncing the Full Third Tone Too Often

Many learners consistently use the full dipping-rising contour of the 3rd tone in contexts where native speakers would use only the low "half-third." This results in speech that sounds exaggerated, unnatural, and rhythmically awkward.

To address this, pay close attention to how native speakers use the 3rd tone in connected speech. Notice that the full rising-falling-rising pattern rarely appears except in isolation or for emphasis. Practice using the low half-third before other tones, focusing on the dipping quality without the final rise.

As we've explored the mechanics and learning strategies for Chinese tones, let's now address some common questions that often arise as learners deepen their understanding of this essential aspect of Mandarin pronunciation.

VI. Expanding Your Understanding: FAQs and Broader Context

This section addresses frequently asked questions about Chinese tones and provides additional context to enhance your understanding of tonal languages more broadly.

1. Definitional Q: What truly distinguishes the 'neutral tone' from the four main Mandarin tones?

Unlike the Chinese four tones, the neutral tone has no fixed pitch contour of its own. Instead, it's characterized by brevity, lack of stress, and a pitch that's largely determined by the preceding tone. It's essentially defined by what it isn't—a distinct, stressed syllable with a prescribed pitch pattern. The neutral tone is short, light, and subordinate to the toned syllable that precedes it, functioning somewhat like unstressed syllables in English but with context-dependent pitch.

2. Grouping Q: Beyond Mandarin, what other major Chinese varieties rely heavily on tones?

Tones are fundamental to virtually all Chinese language varieties, though their number and characteristics vary significantly. Cantonese, spoken primarily in Hong Kong, Macau, and Guangdong province, features six to nine tones depending on how they're classified. Hakka, Min (including Hokkien/Taiwanese), and Wu (including Shanghainese) also utilize complex tonal systems. Each of these languages has developed distinct tonal patterns that, while related to Mandarin's system, have their own unique characteristics and rules. Standard Chinese phonology includes the four main tones plus the neutral tone we've described in this guide.

3. Comparative Q: How does the challenge of learning Mandarin tones compare to learning grammatical gender in languages like French or German?

Learning Chinese tones and grammatical gender present different types of challenges. Tones primarily involve developing auditory discrimination skills and muscular control for pronunciation—physical abilities that may be completely new to speakers of non-tonal languages. In contrast, grammatical gender often involves memorizing seemingly arbitrary categories and applying agreement rules consistently. Tones directly impact immediate comprehensibility—a wrong tone can make a word unrecognizable—while gender mistakes rarely prevent understanding but affect perceived fluency.

4. Boolean Q: Is it possible to communicate basic ideas in Mandarin without perfect tones?

Yes, basic communication with imperfect Chinese tones is possible, particularly in predictable contexts where the meaning can be derived from situation, gestures, or limited vocabulary options. Native speakers often mentally "correct" tonal errors when the context is clear enough. However, this accommodation has severe limitations. As conversations become more complex or abstract, tonal accuracy becomes increasingly essential. Relying on contextual cues rather than tonal precision severely restricts your ability to communicate effectively and places an unfair burden on your listeners.

VII. Integrating Tones Seamlessly: The Path Towards Natural Mandarin Speech

As we conclude our exploration of Chinese tones, let's focus on the ultimate goal: making tones an integrated, natural aspect of your Mandarin speech rather than a separate skill that requires constant conscious effort.

1. Consistency is Your Ally: Making Tone Practice an Ingrained Habit

Mastering Chinese tones requires regular, consistent practice rather than occasional intensive study. Short, focused daily practice sessions are far more effective than marathon weekend sessions. Make tones a non-negotiable aspect of all your Mandarin learning activities—vocabulary acquisition, listening practice, speaking exercises, and even silent reading (by visualizing the tone marks or contours).

This consistent approach helps create neural pathways that gradually make correct tonal pronunciation more automatic and less cognitively demanding. When you learn Mandarin tones systematically, you build a solid foundation for all future Chinese language development.

2. From Conscious Effort to Automatic Skill: Embracing the Learning Curve

Initially, producing correct Chinese tones requires significant conscious attention and effort. You may need to think explicitly about the pitch contour of each syllable, which can make speaking feel slow and laborious. This stage is normal and necessary—embrace it rather than getting discouraged by it.

With continued practice and exposure, tones gradually shift from the realm of conscious effort to unconscious competence. Just as you don't consciously think about tongue positioning for each sound in your native language, eventually Chinese tones become an integrated aspect of Mandarin words in your mind rather than an add-on feature requiring separate attention.

3. Final Thoughts: Tones as the Key to Unlocking Fluent Communication

Throughout this guide, we've emphasized that Chinese tones are not merely a decorative feature of Mandarin but its very heartbeat—the essential component that gives life and meaning to the language. Mastering Chinese tones is the key that unlocks genuinely effective communication, allowing you to both understand and be understood with clarity and precision.

The journey to tonal mastery is challenging but immensely rewarding. As your tonal accuracy improves, you'll experience breakthrough moments when native speakers suddenly find you much easier to understand, and Mandarin conversations that once seemed impenetrable gradually become accessible. This transformation makes all the effort worthwhile, opening doors to meaningful connections with over a billion speakers of the world's most widely spoken first language.

Remember that every successful Mandarin speaker was once a beginner who struggled with tones. With patience, persistence, and the structured approach outlined in this guide, you too can decode Chinese tones and make them an integrated, natural part of your Mandarin communication skills.

Hi I'm Chloe, and I am currently serving as an Product Content Administrator at Prep Education. With over five years of experience in independent online IELTS study and exam preparation, I am confident in my ability to support learners in achieving their highest possible scores.

Comment

Premium content

View allPersonalized roadmap

Most read